If you’re walking near the dargah of Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya in the neighbourhood of Nizamuddin Basti in Delhi, you might cross, but not notice, a grey door with a grey metal flower knob and no signage. If you are passing by on a Tuesday afternoon, you will, most likely, notice a group of children in descending order of height gathered outside the grey door. The children dart in every five minutes, running up the stairs behind the door that lead to the first and second floors of the building. They leave trails of chips, flowers, coins, plastic toys, and small footwear in their wake. They are requested by someone inside the building to return at 2 pm. The children huddle around the last flight of stairs, refusing to go back all the way down. Anticipation fills the air. At 2 pm sharp, music plays and a big yellow door on the second floor is flung open.

The children take off their shoes and arrange these in a narrow balcony on the same floor. Someone is sitting on the stairs with a register—they ask each child to write their name under a specific symbol. Someone else draws the little symbols corresponding with the names in the register on the children’s hands. The children look at these ‘tattoos’ and speculate about what they will mean for their afternoon.

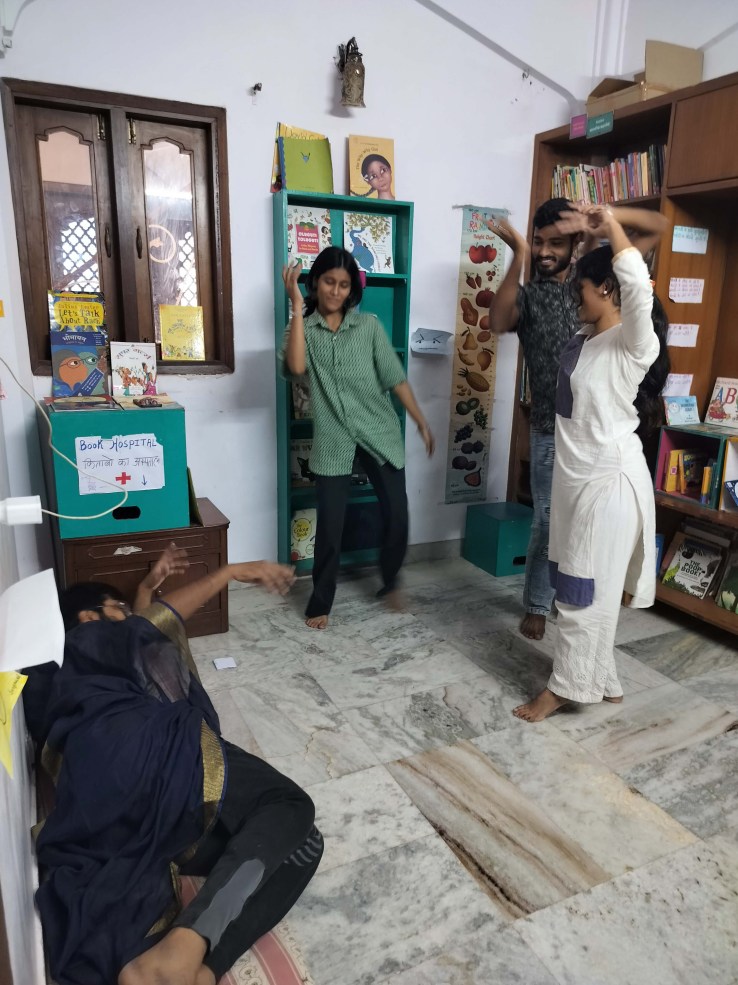

By then the music is too compelling, and the space fills with dancers, choreographers, and singers, all vibing to the music. The graphite-coloured walls in the rooms and the corridor are soon covered in fanciful florals, faces, names, friends’ names, Indian flags, strange creatures, buildings, and favourite book covers—all in multi-coloured chalk.

Chalk art in the library.

One room has a serious carrom game in progress, with multiple players lining up for their turns. In the same room, children are twirling, walking on their hands, chasing each other, throwing and catching balls, hiding in boxes, doing stray homework, or just sitting and enjoying a chat.

A carom game in progress.

In another room, there is a collection of books, vividly colourful ones. There are mostly picture books—English, Hindi, bilingual, and wordless, fiction and non-fiction, comics, poetry, magazines, plays, novels, award-winning books, handmade books, and, the children’s most favourite kind, fairy tales. Some of the shelves are theatre boxes—wooden blocks that double up to make set pieces, seating, props, and storage. Some wooden boxes are the favourite reading nooks of the smaller children.

Wooden boxes as reading nooks.

In another room a mishmash of wooden blocks, Jenga, toy cars, puzzle pieces, a doctors’ set, a kitchen set, flash cards, stuffed toys, hand puppets, and board game objects are spread out all over the floor. In the hands of players of all ages, new games constantly emerge from the corpses of old ones.

When a half hour of this freewheeling play has passed, a jangly trumpet sound announces that it’s time for the children to get into their groups. Different rooms have different symbols (‘tattoos’) on their doors. The children make their way to their respective rooms.

Toys set up for free play.

It’s open library day, and the library programming has officially begun in Khwāb Ghar—the community library and art centre run by Aagaaz Theatre Trust.

Khwāb Ghar (lit., house of dreams) is nestled inside Imam House, a grand old building full of arches, long corridors, cool breezes, and inexplicable windows. Aagaaz has been active in Nizamuddin Basti for over fifteen years, exploring theatre and the arts with a cohort of children from the Basti, who eventually grew into the artist-facilitators that run Aagaaz today. The eight artist-facilitators, who are in their early twenties, work with children and young people from the Basti, while also actively devising and performing plays in the professional theatre circuit. This core group makes up the Aagaaz repertory.

Screening of the short film Mukund and Riaz (dir. Nina Sabnani, 2005).

Back in 2022 when Aagaaz offered me the opportunity to build a free community library for children with them, I said yes. I don’t think we realized, at that point, the scope of what we were intending to do.

I had grown up, like so many lonely people, as a child of libraries. Reading came easy, thanks to my mother’s afternoon read-alouds, seeing books at home as a matter of course, and having parents always willing and eager to take me to the library.

Day-to-day life often felt overwhelming, and libraries became a secret parallel world that was just mine. Those libraries were designed to be experienced in isolation and silence. Seeing other people there was rare, seeing young people even rarer. Most of the collections weren’t meant for children. The books rarely had characters who were Indian, certainly never Indian children. The education they provided me was almost exclusively from a European perspective. I knew myself to be a ‘little savage’ and gritted my teeth, even as I delighted in the possibility of fairies, living toys, magical trees, detectives, mythical creatures, cucumber sandwiches, and high tea. Every library felt like a continuation of the previous one—each a relic of some long-dead world, and I, an archaeologist greedy for its unsuitable stories. I spent free time at the age of ten memorizing Tolkien’s nonsense poems, thinking how cool it made me.

You can imagine I spent a lot of time alone.

Even as a slightly more integrated teenager, young adult, and adult, reading was something I did by myself.

My first and last full-time job was at a children’s library—an experience equal parts romantic and disillusioning. I was one of the few employees there who read often and for pleasure. It was through the challenges the library faced in making reading an everyday practice that I understood for the first time that readers don’t pop into the world fully-formed—cosy and bookish with their little cups of tea. They emerge from structures of access and opportunity often available only with class and caste privilege, among others.

The experience of libraries for Aagaaz’s repertory members had been very different from mine. They knew libraries as mostly threatening, hostile, and exclusionary spaces. Books were associated with school and its pressures. The library was where they were forced to read newspapers and thereby become better children. Their government school library had all the books under lock and key, and they were only allowed to touch them when there was an inspection and teachers assigned them the task of cleaning the books. One repertory member shared that their main memory of the library was being asked to put their heads down on the desk and stay in silence for the entire library period. Another shared how a library in the adjoining neighbourhood of Nizamuddin West (one of the most expensive and exclusive neighbourhoods in south Delhi) had staff who would bar them from entering, just by looking at their clothing and deciding that they ‘were not the right kind of crowd’. The very idea of reading for pleasure was strange.

What was common to my experience of libraries and that of the repertory was the indifference or absence of adults to recommend books or shape our reading journeys. Our shared baseline became that books and reading are not necessarily pleasurable or exciting but have the potential to be. Together we decided that we would create a completely different library.

Left: Free play and vibing to music. Right: Facilitators in a spontaneous dance party.

My personal interest and experience lay in bringing theatre into the library. And for Aagaaz, as a theatre group, using play and playfulness felt like the most natural approach towards making the library and its programme. We came up with the name Khwāb Ghar and dreamt it up as a fanciful child-centric library where books would be associated with pyaar, khel, and mazaa—love, play, and fun. Silence would not be enforced, nor would books be cut off from anyone. It would never be a scary or hostile space—instead we would do our best to make it delightful.

Left: Library room chaos. Right: Read-aloud with the projector.

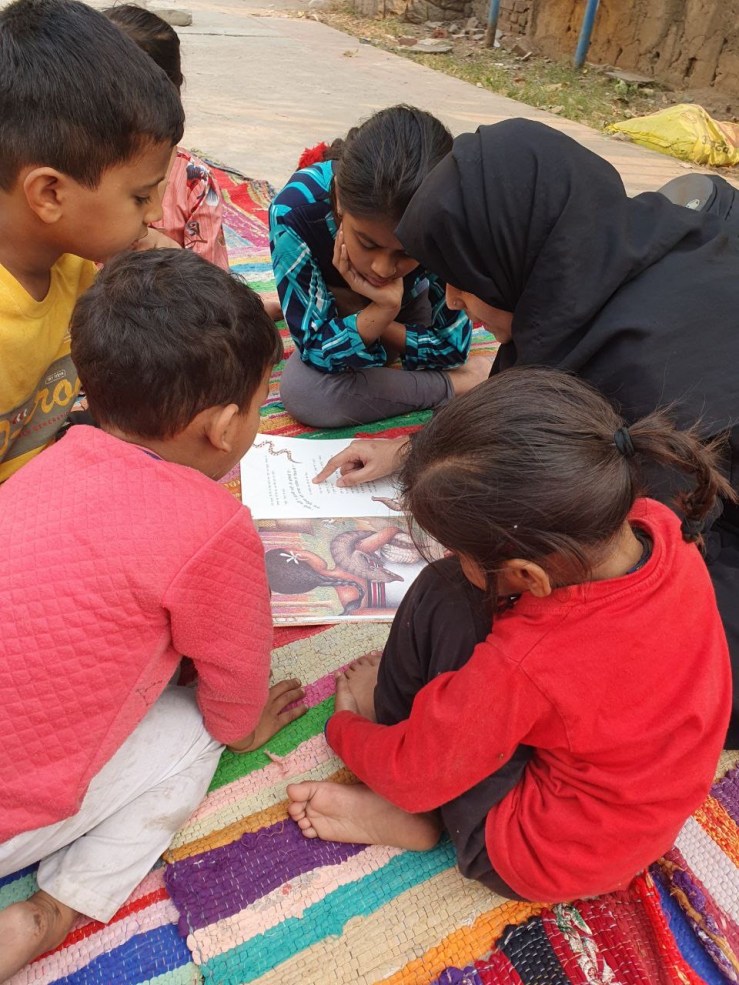

Open library day at Khwāb Ghar, apart from playing, includes browsing and reading, a read-aloud, story-telling session, or performance by the facilitators, and an arts-based activity. Themes are shaped by the season, the needs of our audience at the time, relevant events or happenings in the neighbourhood, or simply something that feels exciting.

For instance, the majority of the Basti’s residents migrate seasonally. So around September, many people return to their villages. During one of these times, the theme of our open library was ‘going home and returning’. We looked at a picture book from the 1980s called My First Train Journey, and one room was converted into a train compartment, complete with running scenery projected on the wall. Each child was given a train ticket when they entered the library. A stern ticket collector (in full costume) checked the children’s tickets before they entered the ‘train room’. A ‘chai-seller’ burst into the room and distributed Rooh Afza in a kettle at some point. The library was decorated with a train of books each of which showed different types of journeys. One room had a dynamic movement and imagination game where people recreated their journeys to the village and then back to the city.

Detail from ‘house building’, using books and other materials in the library.

Khwāb Ghar started with a soggy wooden trunk and 55 books in the collection. Two years down the line, we had shifted into a new space, made it our own, grown our collection of books (over 1,400 at the moment), toys, and other resources, created infrastructure, begun borrowing and lending, instated consistent weekly library programming, and put administrative processes into place with tears, confusions, and scary excel sheets along the way. We gained and lost new books, members, visitors, allies, plants, and wildlife.

All of it has been unexpected. So, it makes sense that nothing about Khwāb Ghar is quite what you’d expect.

The floors where Khwāb Ghar is located used to earlier function as a guesthouse for visitors making annual pilgrimages to the dargah, and so it boasts many, many bathrooms, perhaps the most in any library I’ve known—nine! And this is very exciting for children, young and old. Using the washroom is one of the most popular activities in the space, especially bathing in the sink and switching the lights off when one’s friends are inside.

In the winters we do pop-up libraries on the terrace and our reading and playing is punctuated with the whistles of pigeon fanciers training their pigeons for annual races, while kites wheel overhead.

Left: A winter pop-up library in a park. Right: Pop-up library on the roof.

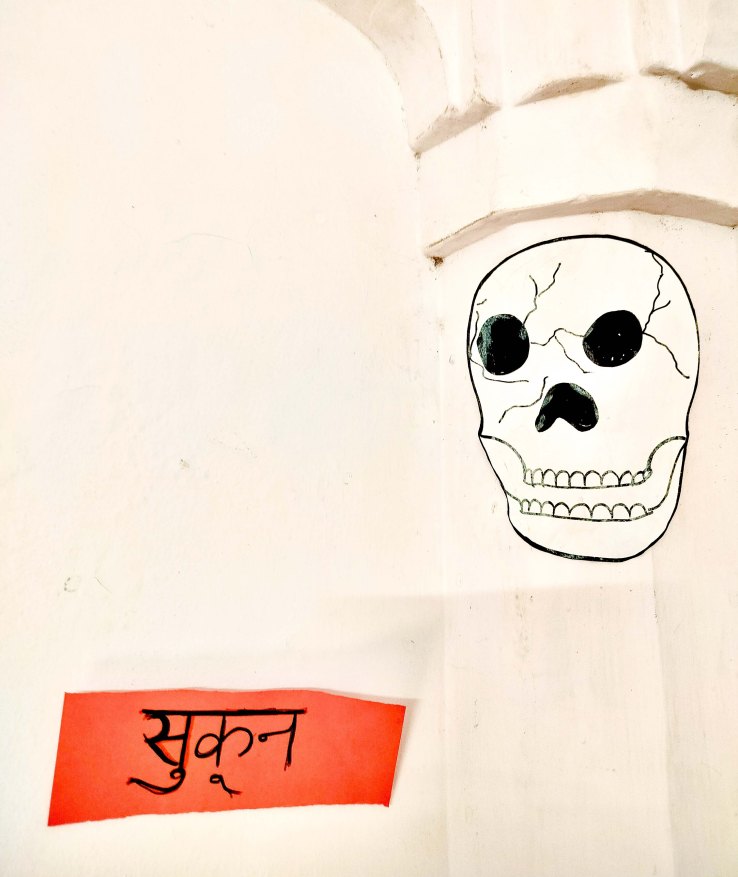

Our library has featured, at different times, an ER for damaged books with emergency repair ’surgery’ by ‘book doctors’, Charlie Chaplin film screenings with all the facilitators as clowns, a Halloween library special with ghost stories and all the facilitators as ghosts and monsters, the nine rasaas personified (sorrow, love, peace, rage, delight, disgust, wonder, fear, and bravery) through different books, a Khwāb Ghar ka Nehru writing letters to the children and leaving them new books, a rogue Santa Claus holding a dance party, and an election campaign.

Left: Ambedkar in the library. Right: Kasturba Gandhi in the library.

All of this has involved intense excitement and participation from the children and young people who are our members. We have had children share bloodcurdling ghost stories, react to performances in character, borrow a set of speakers and mic from a relative for an open library day, and generally bring double or triple the energy we anticipated to any of these open libraries. Most of all, they read by their own choice, together and by themselves, and with the facilitators. They request favourite books, actively spend time browsing, listening, and talking about the things they read and how it connects to their day-to-day lives.

An unintended corner in the library, after the Halloween party.

Our readers and visitors are continuously doing unexpected things as well: Like the time a two-foot-tall police-woman walked in and startled us by running at high speed down the corridor (it was a three-year-old child in a remarkably detailed costume). Or the time a child brought a pink chick to the library that we kept in one of our boxes. Or the time someone hid a comb behind a shelf of non-fiction books. Or the time a painstaking model building was recreated using books as the building blocks and toys as the characters. Or the time all the adolescent boys pooled their resources together and gifted the library carrom pieces for the carrom board because they’d been getting lost. Or the several months that shayari books became all the rage among older children, and collective poetry recitations and songs became a common sight in the shaam ki library (evening library). Or the time a boy decided to change from shorts to trousers to get ‘ready’ for shaam ki library. Or the time we found an exquisitely illustrated post-it scrunched up behind some shelves that showed two children with a ball and the line ‘khelna sab ka haq hai’ (‘the right to play belongs to everyone’).

Amid these delights, we do face challenges—scarce resources, lost books, missed opportunities, mistakes in planning, the administrative oddities of creating the experiences we try to. And questions keep recurring: What are we setting out to do? What’s the point if our members keep leaving the city?

At the same time, every library day, every activity, every unexpected incident also reminds us how much the space has come to belong to those who come here.

And I can no longer think of a library as a place of loneliness.

—Alia Sinha

Alia Sinha is an illustrator, theatre practitioner, and the library programme director at Aagaaz Theatre Trust. She loves mushrooms, bees, books, and practical jokes.

Check out Alia’s work @minor_grace

Know more about Aagaaz Theatre Trust @aagaaztheatretrust and @aagaazrepertory

Complement this essay with Samprati Pani’s ‘Of my shahar and its stories, or how to love an “unloved” city’, a dialogue with the book My Sweet Home: Childhood Stories from a Corner of the City, by Samina Mishra, Sherna Dastur, and the children of Okhla, which portrays the rich, textured everyday life of children and their ways of seeing their neighbourhoods and the city.